Many University-wide initiatives have grown out of Loyola’s Solutions to Environmental Problems (STEP) course: the apiaries, the Loyola station farmers market, and the campus-wide bottled water ban. However, the biodiesel program is the one that has been a permanent fixture for over a decade and caught the attention of the EPA, earning it a Safer Choice Partner of the Year Award in 2015.

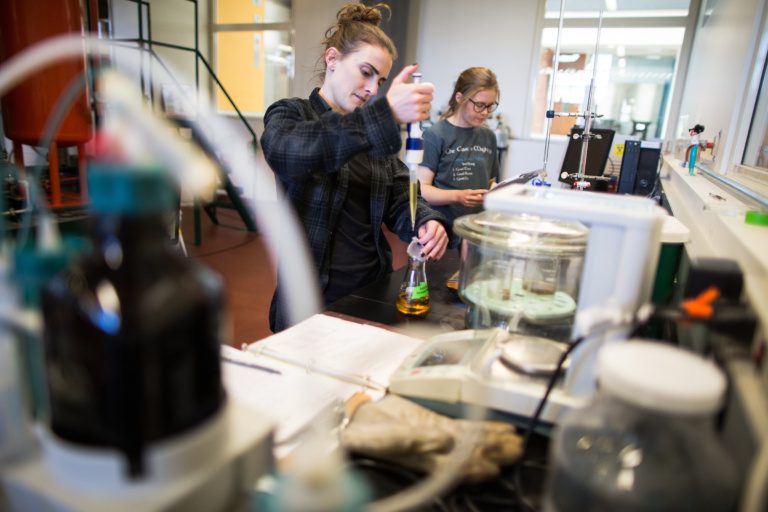

The biodiesel fuel production process hasn’t been a static one for the past 10 years though. Zach Waickman, the lab manager, and his students continue to make the business more energy and cost effective. One of the biggest successes has been BioSoap, which uses glycerin, one of the chemicals left behind from the production process. The hand soap has been used in the restrooms on Loyola’s Lake Shore and Water Tower campuses since 2016. The lab’s other “byproduct” products have included patio torch fuel, windshield wiper fluid, and fertilizer in the past—however when a new idea can’t become a viable part of the business, the team stops production and tries something new.

The STEP-initiated program began in a classroom in 2007 and today is housed in the Searle Biodiesel Lab, which was named when the Institute of Environmental Sustainability (IES) was launched five years ago.

How biodiesel fuel is made

STEP 1

The process itself for biodiesel production isn’t simple, but it’s still completely operated by students. The program collects used cooking oil from over a dozen institutions across Chicago, including the Field Museum and Northwestern University, and turns it into a self-sustaining, sustainable business.

STEP 2

The fuel-making process begins in the dining halls. Aramark, the organization that runs food services on campus, saves the leftover frying oil—and once a week, Loyola’s partner Green Grease Environmental collects the waste vegetable oil. The oil is heated and filtered to remove leftover food particles and water—and then the filtered material is sent to anaerobic digesters. This turns it into nutrient-rich soil and natural gas.

STEP 3

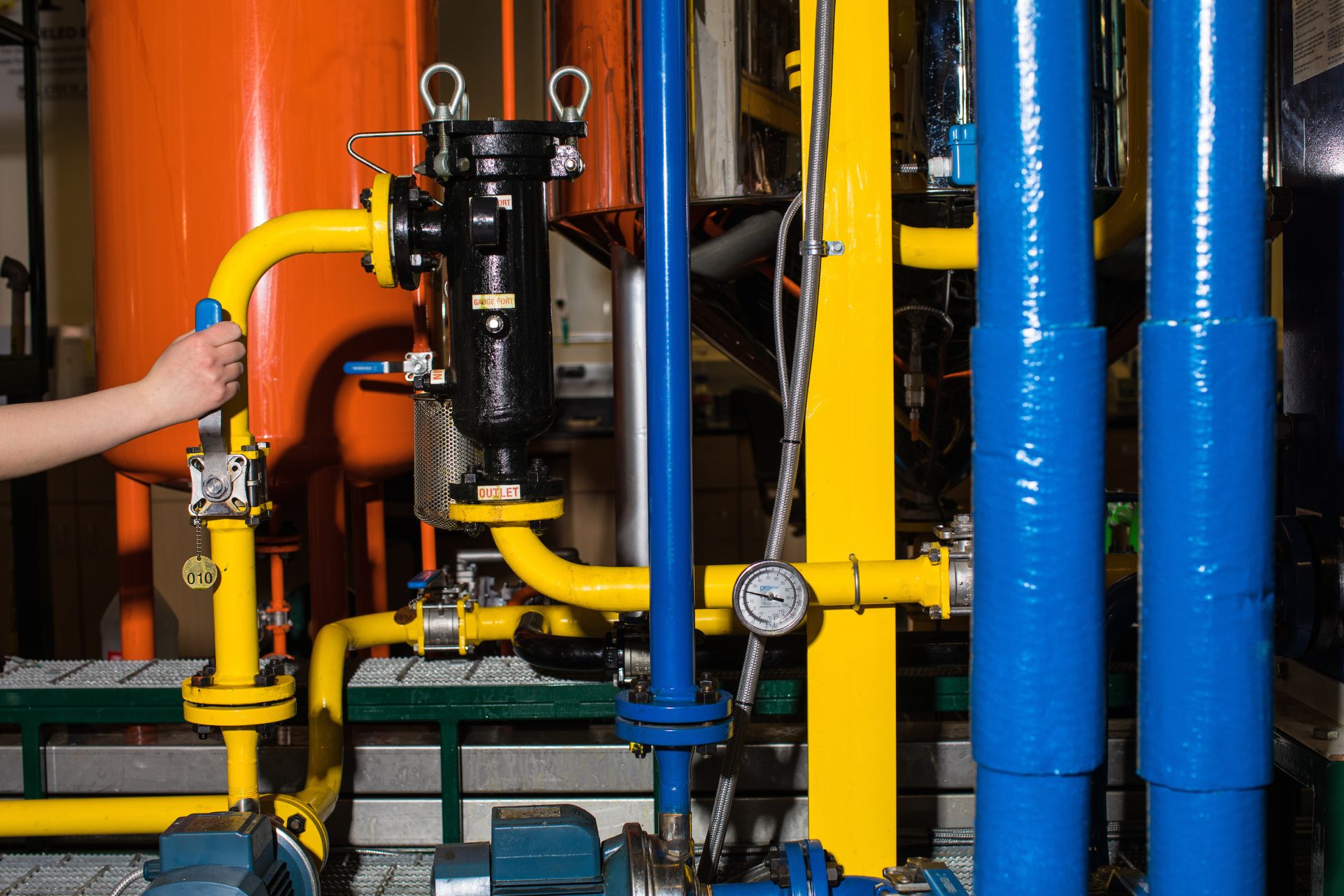

The cleaned vegetable oil gets delivered—600 gallons at a time. To start the production process, around 350 to 375 gallons of vegetable oil are pulled out of the holding tank and sent to the processing tanks. Students pull a sample to test for contaminants like water, sediment, and free fatty acids. Then the oil gets heated up using the boiler in IES.

STEP 4

Potassium hydroxide and methanol are added to the oil to start the chemical reaction—transesterification. Potassium hydroxide acts as the catalyst and splits the oil molecules. It isolates the hydrocarbon chains from glycerin. The methanol forms a new, stable biodiesel molecule, known as fatty acid methyl ester. Then students let the mixture sit for 24 hours while the denser glycerin settles in the tank.

STEP 5

The glycerin is drawn off the bottom and pumped into a separate temporary holding tank. Crude, unrefined biodiesel remains. The next step is to remove leftover methanol from the biodiesel. Waickman says improvements to their equipment have made it so they’re able to reuse the methanol again for the next round of biodiesel production.

STEP 6

Water is added to draw out any contaminants, and students pump in compressed air to drive any remaining water out. Now, the pure biodiesel is pumped into a final holding tank. Students take a sample and test more than a dozen fuel characteristics to ensure the biodiesel meets industry standards.

STEP 7

Loyola’s biodiesel is used to help power its shuttles between the Lake Shore and Water Tower campuses. As of this year, more than 26,000 gallons of biodiesel fuel have been produced since 2007—enough to take 48 trips around the equator.

Read more stories from the School of Environmental Sustainability.